PRESS RELEASE

Resurrecting another lost master

|

|

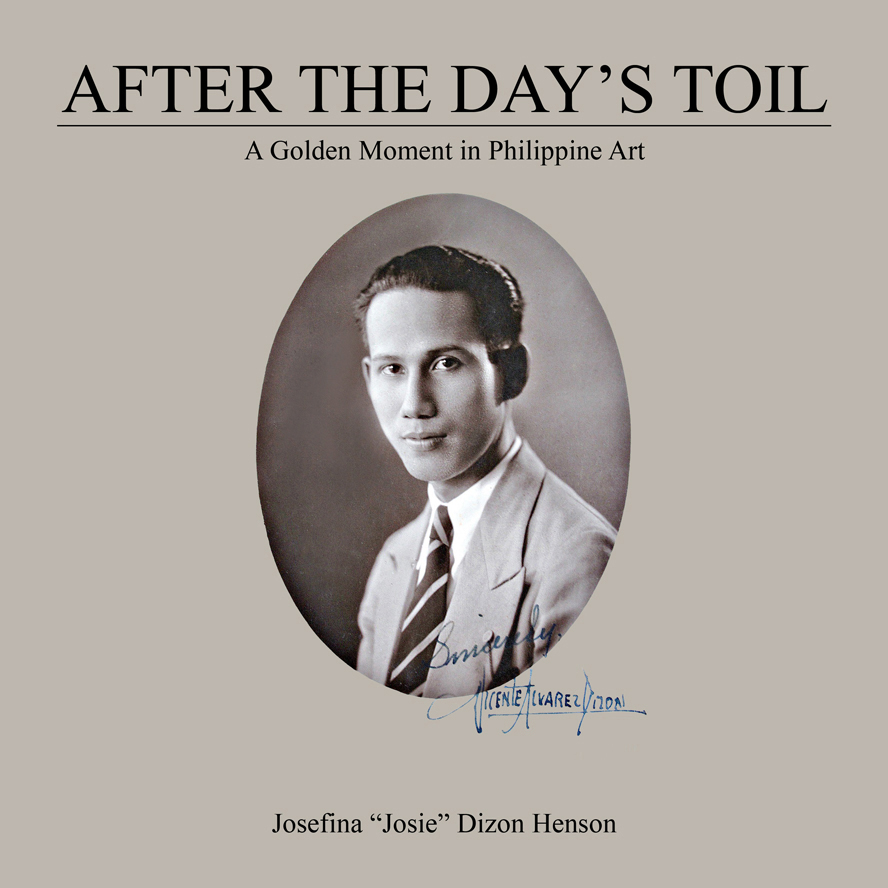

Vicente Alvarez Dizon, 1905-1947

On this Easter Monday, a kind of resurrection story seems to be in order. A few months ago, I wrote a piece about the late painter Constancio Bernardo, a lost master and pioneer of Philippine modernism whose life’s work was then about to be celebrated with a centennial retrospective at the Ayala Museum. Little did I know that — a few weeks later, and thanks to a chance encounter at a literary festival — I would learn of yet another and largely forgotten hero of early 20th century Philippine art.

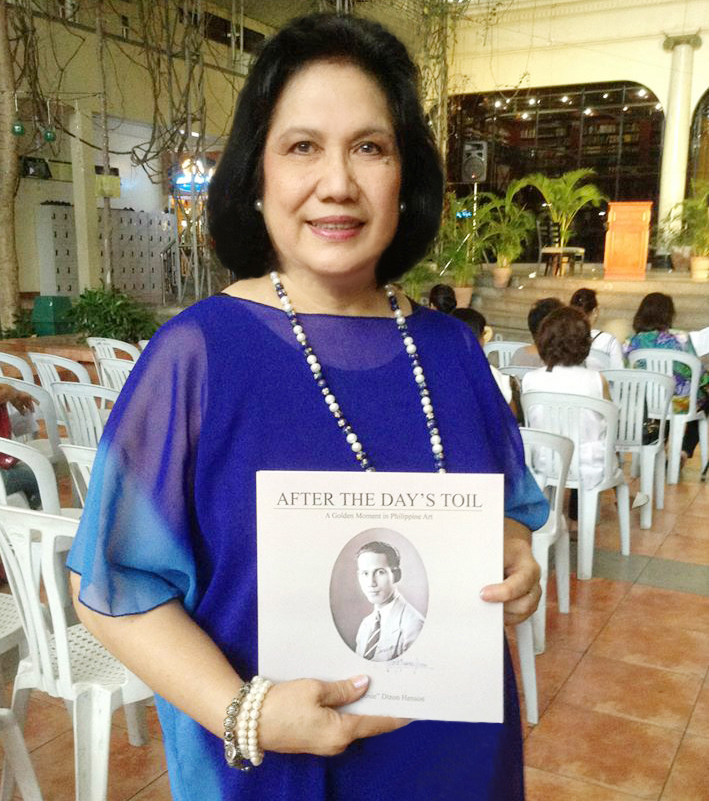

The venue was the Taboan Writers Festival, which we held this year in Subic, with closing ceremonies in Clark Field. It was at Clark that I met Josie Dizon Henson — a painter, writer, and community leader who gifted me with a pair of books she had written. One was a study on Kapampangan orthography, of more scholarly interest; the other book, which caught my fancy, was a slim but substantial, privately published volume titled After the Day’s Toil: A Golden Moment in Philippine Art, a biography of her late father, Vicente Alvarez Dizon and an account of his long-lost masterpiece.

Even at first mention, the name rang a bell in my mind. Two years ago, while doing research for a biography of the late nationalist thinker Emmanuel Q. Yap, I had met (at least by email) a painter named Daniel Dizon, one of Manoling Yap’s boyhood friends. Reminiscing on his friendship with the Yaps, Dan Dizon happened to mention the fact that his father had himself been an accomplished artist — so accomplished that he had won over Salvador Dali in an international competition in the US before the war. That amazing feat — and its doer, Vicente Alvarez Dizon —stuck in my memory. More on that Dali story later.

I had never heard of Vicente Alvarez Dizon before, and as it happened, I would not hear of him again until I met his daughter (and Dan’s younger sister) Josie in Clark. Hearing her name, I made the connection to Dan and to her father, and she seemed delighted to learn that I knew something about her father, and brought me a copy of her book. I set the book aside for a more leisurely read, and when that opportunity arose recently, I found myself engrossed by its account of another extraordinary Filipino life.

Born in Malate, Manila in 1905, Vicente graduated with a diploma from the School of Fine Arts with high honors in 1928. His talent got him a scholarship to Yale in 1934, a sojourn from which he emerged not only with his BFA but also with diplomas in Advanced Painting, Museum Administration and Art Appreciation. Back in Manila, he taught at UP, Mapua, and the National Teachers College; for the rest of his brief life, Dizon would become a staunch advocate of art education and art scholarship, tirelessly lecturing on art subjects around the country.

But his finest hour — the “golden moment” Josie’s book refers to in its title — was likely the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939, an ambitious, visually opulent panorama that rivaled the New York World’s Fair that opened the same year on the opposite coast of America.

Within the exposition, International Business Machines, already an industry giant under its founder Thomas Watson, decided to sponsor an international art exhibition and competition featuring artists from 79 countries where IBM did business, including the Philippines. The Philippine pavilion in San Francisco actually displayed two other works by young Filipino masters, murals by Victorio Edades (assisted by Botong Francisco) and Galo Ocampo. But as fate would have it, it was Dizon’s painting that IBM chose to represent the Philippines.

The painting had been Vicente’s thesis project at Yale. Typical of its time in its evocation of a rustic, romantic countryside, the painting depicted a Filipino family — father, mother, son, carabao, and other farm animals — heading for home at the end of another working day. Because he worked on it at Yale, he had to use Caucasian models for his studies, but replaced the faces with their native counterparts in the final work. He apparently took it home upon graduation, because it was in Manila where IBM’s Philippine representative, Kevin Mallen, saw and bought the painting for IBM, which shipped it to America for the competition. When the results were announced, Dizon had won first prize, followed by Spain’s Salvador Dali and by the American Robert Philipps. (Coincidentally, at the other global fair in New York that same year, another Filipino, Fernando Amorsolo, also won first prize for his painting “Afternoon Meal of the Workers.”)

But that’s not where the remarkable story of this remarkable painting and its creator ends. Vicente himself, sadly, would die young and penniless in 1947 at just 42, afflicted with tuberculosis, a condition that, according to Dan, also ravaged the family’s finances. His masterpiece and legacy lived on — although it was almost lost.

In October 1980, the Batangas-born Filipino-American physician, Roger Pine, received a letter at his home in Princeton, New Jersey from a New York art dealer informing him of the availability of a painting with a Filipino theme titled “After the Day’s Toil,” 40 x 53 inches, signed “V. A. Dizon, 1936.” Would he be interested in looking at and possibly acquiring it? The dealer sent a transparency of the painting along.

The painting had last been seen by the Dizons in 1952, when it had been shipped from the US to Manila on loan from IBM for a local exhibition. And then it vanished. Further inquiries produced no leads other than the name of a New York gallery, which had no records of it.

When Roger Pine received the invitation from his dealer, he felt an instant connection to the painting, having grown up in a family of farmers. He knew nothing about the painting, the artist, nor its provenance, but he did know, especially after seeing the painting itself in New York, that he just had to have it. The dealer — who said that he had earlier tried to interest the National Museum in Manila to no avail—let the Pines have it on installment. It was also only in New York that Roger Pine realized that he had found and bought a long-lost prizewinner.

Next came the trans-continental search for the painter’s family — not an easy task in those pre-email, pre-Google days. It eventually took 25 years and a bit of luck — a dinner conversation during one of the Pines’ visits back in Manila — to connect the Pines with the Dizons. In 2006, the two families met, and the following year, two generations of Dizons trooped to Princeton, New Jersey to visit the Pines and to see, once again, Vicente’s painting. It was a tearful but joyful reunion, the kind of happy ending that deserves to be written about in a book. That’s what Josie Dizon Henson has done.

Vicente Alvarez Dizon, artist who won over Dali, remembered in book

By Tonette OrejasInquirer Central Luzon

JOSEFINA Henson before her father’s winning work

ANGELES CITY—Josefina Henson has scant memories about her father, artist Vicente Alvarez Dizon. She was only 5 years old when Dizon died of tuberculosis in 1947 at the age of 42.

But Henson, now 71, shared her discoveries about her father’s legacy through a book that compiles the narratives of his contemporaries and disciples.

Her book “After the Day’s Toil” is a “timely reminder to this generation about the work of an excellent and pioneering artist who brought honor to his country and people, and who contributed greatly to the formation of generations of artists, myself included, at the College of Fine Arts of the (University of the Philippines),” wrote Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera, National Artist for Visual Arts, in the book’s foreword.

The book’s publication was an attempt to “rescue the legacy of a life so unjustly cut down [by illness] at the height of its powers,” according to the book’s editors Juliet C. Mallari and Alex M. Dacanay.

At the book launch in Holy Angel University (HAU) on Tuesday, HAU president Arlyn Villanueva described the 130-page book as a “loving tribute” by a daughter, who needed to pluck Dizon out of obscurity.

Henson as well as her elder brother, Daniel, are both painters, who championed their father’s ideas through decades of craft and research.

JOSEFINA Henson

Dizon carved a golden moment for Philippine art when he placed the country at the top of the world’s biggest art competition in 1939. He won the top prize in the Golden Gate International Exposition, which opened on Feb. 19, 1939 in San Francisco, California.

His painting “After the Day’s Toil” adjudged the best among the works of 77 artists, including that of Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali.

The masterpiece, Henson said, was Dizon’s graduation thesis at Yale University where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in fine arts in June 1936. He finished it with distinction in less than two years.

Kevin Mallen, a representative of the International Business Machines in the Philippines, bought the painting and entered it in the contest.

Dizon described his piece this way: “The painting depicts a group of Filipino peasants homeward bound after their toil in the sugar cane fields. They look happy and cheerful and all seem contented in life. All the faces in the picture, including the animals, have varied expressions of gaiety. Even the surrounding landscape has a very cheerful and inviting aspect.”

After explaining techniques like perspective and contrast, Dizon said: “[The] picture also wants to revel in the first place that no matter poor they are, Filipinos dress decently like all civilized peoples of the world; secondly, that the Philippines is rich in natural beauty and worthy of the love and respect not only of her own people but those of other lands; thirdly, that the Filipinos are the only Christian people in the orient, as symbolized by the church in the background; and lastly, that the Filipinos are a happy and peace-loving people as symbolized by the placid river.”

Acquired by a Filipino

Dr. Rogelio Pine, a Filipino cardiologist based in New Jersey, acquired the original painting at the invitation of the Daniel B. Grossman Fine Art Inc. in New York on Oct. 3, 1980.

“Mr. Grossman allowed me to pay in installments, at $1,000 a month, in three years,” Pine told the Inquirer after the launch.

“The painting came to us; we did not seek it,” he said, adding that he established an immediate connection with the painting because it portrayed his humble beginnings in Batangas.

It took Pine 30 years to find Dizon who had been searching for the original masterpiece to fulfill a wish of his mother, Ma. Ines Lutgarda. Pine and Dizon finally met in 2008. An unfinished copy of the original painting and the studies made for it are in Dizon’s possession.

Virginia Flor Agbayani, former associate dean of the UP College of Fine Art, wrote of Dizon’s dream of instituting an arts education at the state university.

The maestro, she recalled, went around public schools doing “chalk talk,” a reference to Dizon’s practice of drawing a line which he eventually used to shape images, to teach arts to young children.

“Maestro Dizon’s vision for Philippine art and the future of Philippine artists was not an elitist undertaking; art should be a source of education and enlightenment open to all, from the elementary grades all the way to the post-graduate levels,” Agbayani said.

Art educator

She said Dizon “spent the meager energy left to him during his remaining years revising the arts education courses at UP.”

Fernando Amorsolo, the painter’s contemporary, chose Dominador Castañeda, who worked with Dizon, to replace him as director of the [now defunct] School of Fine Arts, Agbayani said.

Agbayani said the curriculum made by Dizon and Castañeda “became the basis of the general education course of the future UP school of fine arts in its transition to gaining status as a college.”

Aside from pioneering finger painting in the country as well as doing research and sketches on Filipino costumes, Dizon also advocated for a museum that would be a permanent treasure house of Philippine art works, according to the late artist Galo Ocampo.

Henson said her father also made a visual diary consisting of 39 paintings of life while they were on the run in Pampanga during World War II.

She is preparing to exhibit these works, possibly in time for her father’s 110th birth anniversary in 2015.

“In the end, his love of country overwhelmed even his passion for art,” Henson said. “He believed that hard work, perseverance, family values and love would bring a glowing sense of satisfaction and well-being after the day’s toil.”